Zakariya, our driver, corners hard then comes to a stop whilst winding down the window.

"Do you know Halima who makes the makroudh?" he asks the passerby forced to pause by the minibus Zakariya has put in their way.

"Yes," they reply and turns to face down the road, "she lives that way."

"Thanks," Zakariya replies in Tunisian Arabic. He rolls the window up, checks over his right shoulder to pull out into the traffic and starts driving into it all at once.

We’re running late.

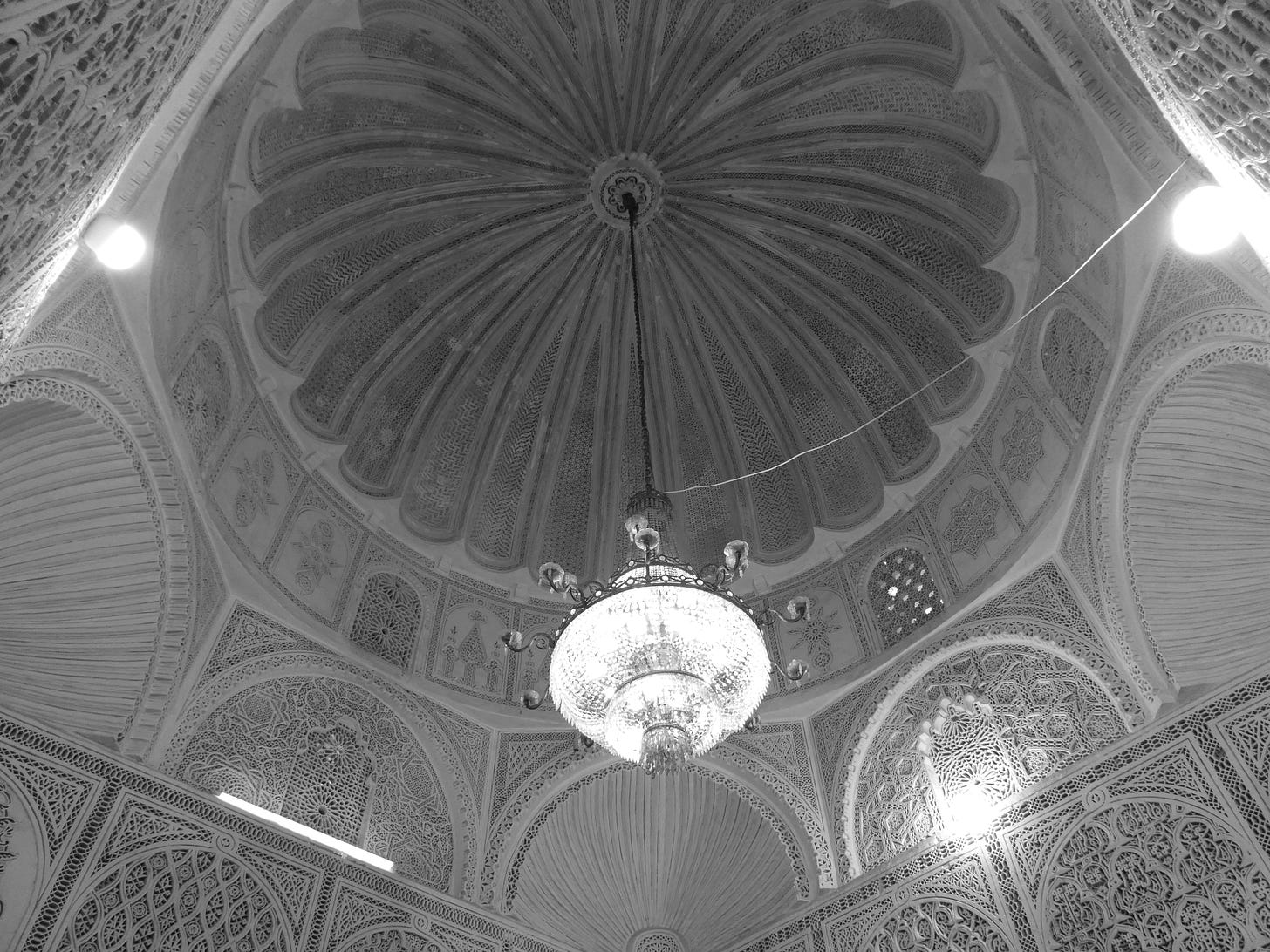

Kairouan in east Tunisia is best known for two things. The first is the Great Mosque of Kairouan, one of the most important sites in Islam, by which I mean either the third or fourth most important depending on who you ask. This seventh century building was the centre of Islamic learning in the region and its architecture served as inspiration for Islamic buildings across the Maghreb. Despite being destroyed and re-built a number of times, the construction itself is remarkable. The 9,000m2 building is partly an open courtyard surrounded by columns, many taken from historical sites in the area.

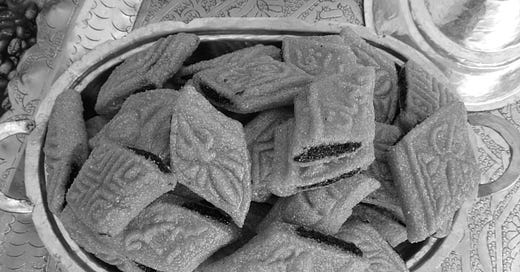

Kairouan's other claim to fame is makroudh - fried and syrup-soaked date stuffed semolina pastries. The designs that are pressed into makroudh are based on the stucco that graces the ceilings and walls of mosques in Kairouan, such as those in the Great Mosque. Looking up at one of these ceilings before going on our hunt for Halima of the makroudh, I found it comforting that I wasn't the only woman in the world who would find food inspiration in the most unexpected places. Leaving prayers, women in Kairouan thinking yeah, that would look great on a pastry, why not?

Which brings us back to Halima.

Halima Berrak is the makroudh maker in Kairouan. Not that she is the only makroudh maker, many others make makroudh at home or in bakeries, but Halima is by all accounts the best makroudh maker. We first meet her in a modest open courtyard where she has set up our open air makroudh lesson. We don our aprons.

"Welcome to my home," she says in fr-arabic. Looking around we recognise the typical set up of a Tunisian home - an enclosed central open space with doors leading off of it. Behind each there is a different room. This way, women could work in the house without being seen from the outside. It's like the inverse of the homes I'm used to in the UK - how do the Joneses know what to keep up with if they can't see what's going on inside?

It's a humbling moment, realising that Halima has literally invited us into her home to share her passion with us.

Halima has thought ahead, weighing out the ingredients that we'll need. She talks us through each as she adds them to her mixing bowls. All this is generously translated by Lamia and Jamie, the founders and absolute gems behind Sawa Taste of Tunisia.

"First there is semolina and flour and into that is added olive oil, melted s'men (clarified butter) and water warmed with a little saffron." She uses her hand to combine them all in a bowl. The resulting dough is pliable, tacky and a gentle yellow. She sets it aside to rest, and brings out the date paste that she has also prepared in advance. This she has spiced with cinnamon, cloves and some other secrets.

"How do you get the patterns?" we ask, remembering what we learnt whilst looking at the ceiling of a mosque earlier in the day.

"These moulds," Halima replies, motioning to the long rhombus shaped wooden moulds on her preparation table. Designs have been confidently carved into the wood, sometimes the same design repeated all the way along the length, others a variety. On the back of each a grooved handle is in the centre to help with the moulding process.

"Some of these are from my family, from my mother and my grandmother. This one," she picks up a mould that is a darker wood with a variety of patterns along the length, "is over 200 years old. And this one," she picks up another that has symbols related to Islam and Kairouan, "has my name engraved on the side. They are very precious to me."

This is not just cooking in Halima's home, then, but being trusted with both the knowledge and tools of generations. We're not tourists, but visitors, travellers that Halima has chosen to share a little of her story with.

She takes some of the date paste, rolls it into a long sausage, then tears off a portion of the dough. This she flattens, then presses the date into it. She eases the dough up and over the date filling and gently rolls the whole lot until it is sealed. Then tipping the whole lot ninety degrees she squeezes along the length and repeats the process again. She chooses a mould, places it onto makroudh and puts her whole weight down through the mould as evenly as she can.

Lifting the mould, the design is revealed. She takes a kitchen knife and cuts along each diagonal line, laying the uncooked makroudh onto a baking tray next to the pot they will be fryed in. Then it's our turn.

Person by person we stand by her side. We each have a review. Some are spoken - “you can come and work for me," for example. When it comes to me, it turns out not all reviews of our attempts are given verbally. I do what I can, rolling and placing the date paste into the dough. Then I squeeze it to bind it all together. I think I'm doing a pretty good job.

At this point, I feel Halima lean assertively against me. She reaches across and takes the dough as she steps into the place at the table I had been at. She says something in fr-arabic, and I look at Jamie for a translation as Halima quickly works the dough to the point at which I can mould it. Jamie laughs, "You need to be more confident," he translates. Confidence with the dough or in life, I wonder, and I go about choosing my mould. The Kairouan inspired patterns take my fancy.

Halima steps aside, I place the mould as centrally as I can and lean down hard. Some of the dough squeezes out of the sides of the mould. Halima reaches, uses the flat edge of the mould to tap the makroudh back into shape and passes me the knife.

Then our collective efforts are fried in a deep saucepan of oil, the makroudh falling over each other in the bubbles to become golden brown.

When deemed ready by Halima with a nod, the warm makroudh is taken with a slotted spoon from the oil and sunk deep into an unctuous sugar syrup until saturated.

"What's your story with makroudh Halima?" we ask.

"I made them with my mother and my grandmother. Then people said that I was good, why don't I sell them, so I opened the shop. If you make with love it is always tastier. Now I can experiment with makroudh - maybe with less sugar, different spices or flours."

We take some of the still warm makroudh. Now by this point I had eaten my fair share of makroudh in Tunisia, but this was something else. The spices in the date sing with the warmth, the semolina dough has a slight crunch amplified by the crevices in the moulded design, they are still crispy from their frying but sticky with the heavenly sugar syrup. I can understand how Halima has become the makroudh maker.

Half an hour later in the minibus there is complete silence. Each of us has slumped in our own way. In our monumental sugar crash there is a gratefulness. Makroudh is often served at the end of a meal and is sold in vast quantities in suqs. Without Halima's guidance we would not have the same understanding of quite what the making and eating of makroudh means. It tells the story of Kairouan, a city monumentally important both in Tunisia and the Islamic world.

Like a Tunisian home, makroudh may be modestly decorated on the outside, a beautiful front door perhaps, but inside hides a secret heart of stories and endless generosity.

Sawa Taste of Tunisia Tour

We were able to meet Halima through the wonderful Sawa Taste of Tunisia Tours. These are foodie tours with a difference - leading with family and women run, ecologically conscious businesses often off of the beaten track.

Website - sawataste.com/eng/

Instagram - @sawatasteoftunisia

Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61553069023239

I didn’t get a precise recipe from Halima, she was too coy about her secrets! I might suggest trying this recipe from Carthage magazine instead.